Beatrice Zhang

Latest posts by Beatrice Zhang (see all)

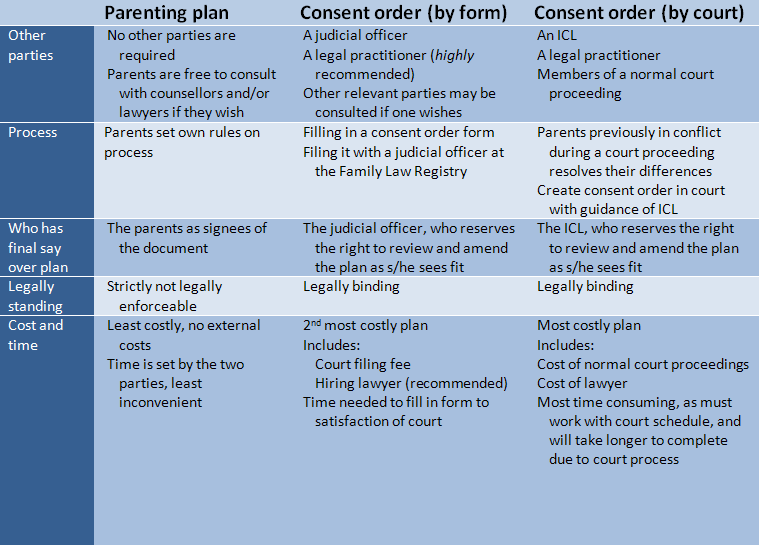

A parenting plan and a parenting order by consent (aka a consent order) are two of the methods available to separated parents who are creating a formal agreement concerning their shared parental responsibilities. Whilst the two methods are both written agreements binding the parties to their agreed roles and responsibilities of child-raising, there is one key difference: a consent order is developed through the court and is legally binding, whilst the parenting plan isn’t. This article will explain the finer differences between the two, so that upon reading this, parents are able to make an informed decision about which method better suits them.

What Are They?

A parenting plan is a formal written document, signed by both parties, which outlines how they plan to raise their child/ren and split the parental responsibility they had once shared. This plan is reached by the two parties together, and is a culmination of the deals and concessions that had to be agreed upon in order to come to a compromise. This is usually done without the external help of a legal professional, although both parties are free to consult one for advice should they feel the need to.

Whilst a consent order is also a formal written agreement detailing the parental arrangements, it differs from a mere parenting plan in that it is filed with the courts and recognised as legally binding document. As consent orders are processed by the courts, the process is more complicated than the process needed to create a parenting plan. The orders can be created in one of two ways: through the filing of a consent orders kit at a family law registry, or they can result mid-way through normal court proceedings, where parents previously in disagreement decide to agree to each other’s terms. The resulting consent order is one that is legally recognised and binding.

The Process

As the parenting plan is simply a plan for the relevant guardians of the child/ren, and is unaffiliated with the courts, the process of creating said plan is far more relaxed than the strict rules one has to follow to make consent orders. As the courts aren’t involved, the parents essentially set their own rules regarding the content, when and how the plan will be created, as they write up the plan themselves. It is recommended, but not necessary, to seek external advice from a counsellor and/or other important adults in the child/ren’s life.

In contrast, the two methods that can be used to create consent orders are both more structured, as there are official legal requirements which must be fulfilled. If the parties opt to use the consent orders kit, they must fill in the forms as per the instructions given in the kit, and submit it at the family law registry, where it is then reviewed and certified by a judicial officer. If the consent orders are developed through normal court proceedings, parents who were in conflict decide to agree to terms. These cases usually involve an Independent Children’s Lawyer (ICL), whose job is to act independently as the child/ren’s representative, and contribute to the development of the consent orders to best benefit the child/ren. A majority of consent orders are agreed to in court, rather than through the certification of consent order form.

Content and Language

Even though the two plans cover much of the same content – how the child/ren’s time will be split, particular responsibilities a certain parent must commit to, child support etc – the structure, length and detail of the parenting plan often differs vastly from those of the consent order.

In a parenting plan, the length and detail are left up to the parents’ discretion, as long as they both agree to the final document. In contrast, consent orders that requireform-filling need to be of a definitive structure, length and level of detail in order for the form to be processed and accepted by the Court. Consent orders that are developed through court will be guided by the court proceedings, and will usually have a structure, length and level of detail similar to one that was submitted through a consent order kit. It is also important to note that unlike the parenting plans, where the parties involved have the final say in what goes in the plan, with consent orders a judicial officer or the ICL has the final say and can add/remove provisions based on whether or not he/she agrees with them.

The type of language used in the documents can vary, as parenting plans are usually written in plain English, without the use of legal terminology, in order to be easily understood and interpreted by the two signees and other relevant relatives in the child/ren’s life. However, since a consent order is technically a legal document, and is written with the help of a legal practitioner, a judicial officer, and/or an ICL, the language tends to be more technical and legal in nature.

Legal Standing of the Respective Plans

An important matter of consideration when choosing a plan is the legal standing of the documents in the case of dispute, or non-compliance. A wronged individual is more likely to achieve justice if they are operating under a consent order. This is due to the legal nature of the order, where the breaking of a parenting order is the same as breaking the law. The court can and will penalise those who break a consent order, through means such as fines, jail time, community service, and compensation to the other party. The court can also order a change to the consent order which doesn’t favour the offender. The full list of penalties is listed in Division 13A of the Family Law Act.

The parenting plan on the other hand, is not a court order, and failure to comply with the plan is not the same as breaking the law in the eyes of the court. As such, parenting plans are strictly unenforceable. Interestingly, while they are less enforceable than consent orders, if a parenting plan is signed by both parties after a consent order, it supersedes the consent order, even though the parenting plan is not legally enforceable.

Time and Cost Required

Another pivotal point when choosing between the two options is the time and cost required to create the plan. For those looking to spend the least amount of time and money creating these documents, the parenting plan is the better choice.This is because while it is recommended that one seeks external advice, creating a parenting plan doesn’t require the services of a legal practitioner, and thus greatly reduces the total cost. Additionally, the fact that this document doesn’t need to be certified as a legal document in court means the cost of the court filing fee is also saved.

In contrast, hiring a lawyer is highly recommended with a consent order, even if it is not developed through court proceedings, as it is a legal binding document, and it would be unwise to sign it without ensuring one fully understands all the legal nuances of the document. This will cost significantly more than hiring a counsellor, but is vitally important to ensure full understanding of the legal rights and responsibilities, and to ensure one is acting within the law. Furthermore, a court filing fee will have to be paid for those created through a consent order kit, in order to get the document certified as a consent order. If the two parties choose not to hire a lawyer, the cost for filing a consent order is $145, as of January 2013.

Due to the nature of the documents, a consent order will also take more time to create than a parenting plan. A parenting plan is completed at the parties’ own leisure, as there is no external party overseeing the creation of the document, nor is there a set date by which one must complete it. Additionally, the parenting plan can be as detailed or brief as the parties choose, thus enabling them to spend as the amount of time they deem appropriate on creating the plan.The consent orders, on the other hand, are developed through the court, and as such must be completed during a specific time frame set by the court. Furthermore, the fact that the document is legally binding, as well as the more complicated language and minimum amount of detail required ensures that more time must be spent perfecting it.

Benefits and Disadvantages of Each

All in all, both plans have their benefits and disadvantages, and choosing one is simply a matter of personal preference and circumstance. The benefits of the parenting plan include the fact that the courts aren’t involved, making the document easier to change (with the consent of both parties) if circumstances change and/or difficulties in carrying out the original plan arise. Additionally, the plain language and lack of legal terminology ensures that the plan is easy to understand by not only the two parties, but other individuals involved in the child/ren’s upbringing, such as grandparents, relatives, and child care workers. Additionally, a parenting order will generally cost less time and money to make.

However, the parenting plan is disadvantaged compared to the consent orders in how legally binding it is. The consent order benefits from having real legal power,which not only acts as a deterrent to breaking the contract, but offers a better means by which to penalise those that do break it. This is as the courts are able to directly punish the offender as a law-breaker. Furthermore, having a court, ICL and/or judicial officer, and lawyer overlooking the creation of the document ensures that everyone’s rights – the child/ren, mother and father – are adequately considered and protected, something that isn’t guaranteed with a self-regulated parenting plan.

However, one way in which it’s possible to have the best of both worlds is to convert a parenting plan to a consent order. This involves starting off with a parenting plan that both parties have agreed to already, and then converting this to a consent order with a consent orders kit, and then asking the Court to certify it. The only additional cost, compared to a normal parenting plan, is the $145 court filing fee. In this way, the parties get the ease and low cost of a parenting plan, with the legal benefits of a consent order.

From the points made previously, it is clear that whilst the information encapsulated within the actual parenting plan and consent order is very similar, the key difference lies in the creation of the document and its legal standing in the event of non-compliance. As such, parents who are looking at creating one of these documents should look at how they want to create it and what degree of legal enforceability they desire.

Family Law Express has sample parenting plans and consent orders in the Sample Legal Documents module, which parents should read over if they are considering either of the two options. We also have factsheets on how to develop parenting plans or consent order up on the website. These two can be accessed at:

www.familylawexpress.com.au/sample-legal-documents and www.familylawexpress.com.au/family-law-factsheets

Family Law issues such as a breakdown of a relationship, divorce, or dispute concerning parenting or financial arrangements can be stressful and traumatic for the parties involved.

Family Law issues such as a breakdown of a relationship, divorce, or dispute concerning parenting or financial arrangements can be stressful and traumatic for the parties involved.

Binding Financial Agreements (BFA) are legally contractual agreements made between either de-facto or married couples before, during or after their relationship, regarding how their financial resources, assets and liabilities will be divided if their relationship ceases. Australian BFAs are recognised by the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)

Binding Financial Agreements (BFA) are legally contractual agreements made between either de-facto or married couples before, during or after their relationship, regarding how their financial resources, assets and liabilities will be divided if their relationship ceases. Australian BFAs are recognised by the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)

Family law proceedings can be both emotionally and financially challenging. Clients involved in family law proceedings generally have both the knowledge and expectation that they may incur significant costs throughout the process.

Family law proceedings can be both emotionally and financially challenging. Clients involved in family law proceedings generally have both the knowledge and expectation that they may incur significant costs throughout the process. Where there is an irretrievable breakdown of a marriage, the party’s can apply for a divorce. An application for divorce is available 12 months after the date of separation. The Court must be satisfied that you and your partner have lived separately for a continuous period of 12 months and are unlikely to resume co-habitation. When approaching the Courts, the parties mainly have two matters which they typically seek a larger slice of; custody of the children, and ownership of property.

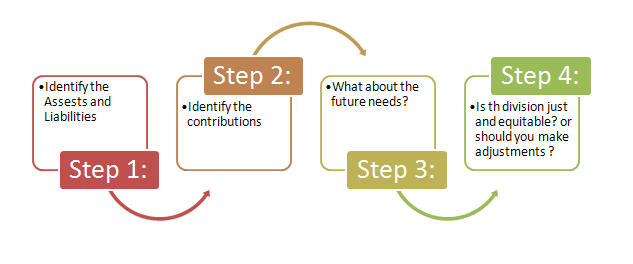

Where there is an irretrievable breakdown of a marriage, the party’s can apply for a divorce. An application for divorce is available 12 months after the date of separation. The Court must be satisfied that you and your partner have lived separately for a continuous period of 12 months and are unlikely to resume co-habitation. When approaching the Courts, the parties mainly have two matters which they typically seek a larger slice of; custody of the children, and ownership of property. Let’s try to identify the elements of the four steps and how the Courts have dealt with each element.

Let’s try to identify the elements of the four steps and how the Courts have dealt with each element.