The period surrounding the loss of a loved one is always a difficult time. When all you want is time to grieve, administering a deceased estate can be seriously challenging.

The period surrounding the loss of a loved one is always a difficult time. When all you want is time to grieve, administering a deceased estate can be seriously challenging.

With this in mind, we have put together a guide to help walk you through the basic steps involved in administering a deceased estate:

Determine whether the deceased left a Will

The first step is to determine whether or not the deceased actually made a Will. There are a number of places that the Will may be located, including amongst the deceased’s personal papers, with their solicitor, their bank, or potentially even with their building society.

If there is a Will, it will generally appoint one or more persons as the Executor. It is the Executor’s role to administer the deceased’s estate, so if you are not the person appointed as Executor, you should advise the Executor of their appointment as soon as you possibly can.

If you are unable to locate a Will, it is important to seek legal advice on who the most appropriate person/s to administer the deceased’s estate would be.

Arrange the funeral

The first step in administering a deceased estate is organising the funeral.

If the deceased left a Will, it may specify their wishes relating to funeral arrangements. On a similar note, it is important to check the deceased’s personal papers, as they may have thought ahead and purchased a pre-paid funeral plan.

If there is no pre-paid funeral plan (or there is, but it does not cover the full cost of the funeral), you can take the invoice from the funeral home to the deceased’s bank and request that they arrange payment from the deceased’s bank account.

Obtain the death certificate

Obtaining the deceased’s death certificate is crucial in administering a deceased estate. The funeral director will usually assist you with submitting the appropriate forms to obtain the death certificate. It can take anywhere from 2 – 6 weeks for the death certificate to be issued.

Identify the deceased’s assets and liabilities

The next step in administering a deceased estate is to identity the deceased’s assets and liabilities.

Go through the deceased’s personal papers carefully to obtain details of their personal assets. It is important to keep in mind that this might include assets held solely in their name, as well as those held jointly with other parties. The kind of assets the deceased may own include real estate, bank accounts, shares, superannuation and life insurance policies.

Similarly, you should check to see if the deceased owed any monies.

Apply for a Grant of Probate (if necessary)

Depending on the deceased’s assets, you may need to apply to the Supreme Court of New South Wales for a Grant of Probate in order to administer the deceased’s estate. A Grant of Probate is a document issued by the Supreme Court which confirms both the Executor’s appointment, and that the deceased’s Will is the most recent one. If the deceased died without a Will (or in certain other circumstances), it may be necessary to apply for Letters of Administration rather than a Grant of Probate.

Generally speaking, if all of the deceased’s assets were jointly owned with another person (more often than not, their spouse), a Grant of Probate is not required. If the deceased owned any real estate or held assets in their sole name over a certain value, then a Grant of Probate will be required.

Ideally, the application for Grant of Probate or Letters of Administration should be submitted to the Supreme Court within 6 months of the date of death. If it is submitted later than 6 months, the court will require an explanation for the delay in the application.

Gather in the deceased’s assets

Once you have the Grant of Probate or Letters of Administration, the next step in administering a deceased estate is to gather in all of the deceased’s assets.

Depending on the assets owned by the deceased at the time of their death, this could include closing their bank accounts, obtaining any death benefit payable under the deceased’s superannuation policies, collecting in the proceeds of life insurance policies, either selling or transferring real estate to the respective beneficiaries and similarly either selling shares or transferring those shares to the beneficiaries.

Make sure the deceased’s debts are discharged and tax affairs are dealt with

Once the deceased’s assets have been gathered in, you will need to ensure that any debts owed by the deceased are paid.

You will also need to ensure that that the deceased lifetime tax affairs are up to date. If the deceased lodged tax returns, this means ensuring that all tax returns are submitted up to the date of death, and that any outstanding income tax owing to the Australian Taxation Office is paid.

Depending on the assets of the estate, the estate itself may also need to pay tax. If this is the case, an estate tax return will need to be lodged and any tax owing paid.

Distribute the balance of the estate to the beneficiaries

Once you are sure that all outstanding debts and tax have been paid, you can distribute the deceased’s assets to the beneficiaries in accordance with the terms of the deceased’s Will. If there is no Will, then Coleman Greig will be able to advise you as to who the beneficiaries of the estate will be, in accordance with relevant legislation.

With people being encouraged to observe social distancing and isolation during the coronavirus outbreak, family lawyers are being asked how best to manage shared custody arrangements.

With people being encouraged to observe social distancing and isolation during the coronavirus outbreak, family lawyers are being asked how best to manage shared custody arrangements. A move into residential aged care can be stressful enough without having to

A move into residential aged care can be stressful enough without having to

The Colt clan’s world was torn apart on July 18, 2012 when a posse of police, and legal and welfare authorities arrived at the family farm and removed twelve of the Colt children.

The Colt clan’s world was torn apart on July 18, 2012 when a posse of police, and legal and welfare authorities arrived at the family farm and removed twelve of the Colt children. Court proceedings about Child Custody, there is a legislative requirement that you attempt to participate in

Court proceedings about Child Custody, there is a legislative requirement that you attempt to participate in  An accused paedophile has been used as an expert by the Family Court in custody disputes that involve allegations of child sexual abuse.

An accused paedophile has been used as an expert by the Family Court in custody disputes that involve allegations of child sexual abuse. Australia’s family law system is failing to protect children by misleading separated parents into believing their children have to spend time with their ex-partner, even if they are dangerous, one of the nation’s largest children’s charities has warned.

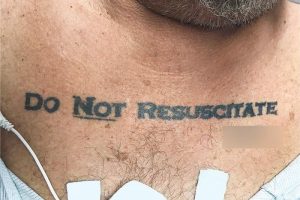

Australia’s family law system is failing to protect children by misleading separated parents into believing their children have to spend time with their ex-partner, even if they are dangerous, one of the nation’s largest children’s charities has warned. The man arrived at the hospital unconscious, without identification, with a high blood alcohol level.

The man arrived at the hospital unconscious, without identification, with a high blood alcohol level.