Muslim women value their membership within their religious community; making them aware of the various options they can access to gain a religious divorce is an important way they can claim their religious rights and freedom. (Samere Fahim Photography / Getty Images)

Both Muslim men and women are allowed to divorce in the Islamic tradition. But community interpretations of Islamic laws mean that men are able to divorce their wives unilaterally, while women must secure their husband’s consent.

In Australia, there are instances where couples divorce under the civil process but the husband refuses to grant his wife access to a religious divorce by withholding his consent, effectively trapping her in a “limping” marriage situation. This means she is divorced under civil laws but still considered by her husband and community to be religiously married and unable to enter a new relationship.

Like other faith communities in Australia, Muslims are able to have a combined religious and civil marriage through a religious leader if they are also an authorised celebrant. When it comes to divorce, however, the civil and religious proceedings must be done separately — civil divorce through the Family Court, and religious divorce through community processes. Although the civil divorce is acknowledged by Muslims as the only legally recognised form of divorce in Australia, the religious divorce is important for its communal and symbolic significance, to ensure that the relationship entered into “in the eyes of God” is now dissolved according to Islamic laws.

It’s not just Muslim women who face difficulties in gaining a religious divorce alongside a civil divorce. Since 1992, there have been numerous submissions and recommendations from both Muslim and Jewish communities seeking solutions for women in “limping” marriages. The Australian Law Reform Commission produced a report regarding this predicament in 1992, followed by Family Law Council reports in 1998 and again in 2001. The main recommendation involved minor legislative changes to remove the barrier to remarriage faced by these women — essentially involving the withholding of a decree absolute until the religious divorce was effected. But the Attorney-General’s office was not convinced that the proposed legislative changes would provide the best solution.

Muslim and Jewish women’s advocacy groups also expressed concerns that such proposals would mean recalcitrant husbands who are not interested in a civil divorce could prevent their wives from receiving either a religious or a civil divorce. Another concern is that husbands will seek to delay or prevent their wives from accessing a civil divorce by insisting that they go through a community process first.

Many of the submissions regarding Islamic divorce stated that women in “limping” marriages are not completely divorced until they gain a religious divorce through community processes, even when they have undergone a civil divorce. My research on Muslim women’s experiences of religious divorce found this approach restricts the avenues by which Muslim women can secure a religious divorce, and doesn’t consider other options available under Islamic laws that a woman can be free of an unwanted marriage.

What I found troubling about this approach was that all Muslim women were positioned as passive subjects that needed to be saved from their “limping” marriage situation rather than as active instigators seeking justice for themselves. In my own family and among many of my friends, I have witnessed numerous instances of Muslim women who married and divorced, in some cases multiple times.

The phrase “not ‘completely’ divorced” in the title of my book does not imply my agreement that all Muslim women are trapped in “limping” marriages — rather, it serves to highlight the dilemma in which Muslim women find themselves. At many levels, from families to friends to community groups to religious authorities, women are told that they are not “completely” divorced unless they have a definitive religious divorce. But how do they decide what is definitive to them?

The purpose of my research, therefore, was to explore and understand how Muslim women in Australia go about determining for themselves what constitutes a “complete” divorce, and how they navigated the challenges faced along the way.

Multiple options for women to divorce

Despite Muslim community perceptions that under Islamic laws women can only divorce with their husband’s consent or by means of community processes, there are in fact multiple options available by which Muslim women in Australia can secure a religious divorce. Derived from the primary religious texts of the Qur’an and Sunnah (sayings and teachings of Prophet Muhammad) and formulated by Muslim male jurists into religious rulings by the twelfth century (six centuries after the introduction of Islam), they have become codified in many contemporary Muslim countries through case law or legislation.

Men can initiate divorce through talaq — which is no-fault — and they do not need the wife’s consent. According to Muslim jurists, this form of divorce is extra-judicial, in that they do not need to declare it before a religious authority. In order to manage registration of marriages and divorces, however, most Muslim countries now require men divorcing through talaq to notify the court.

Is the husband’s consent necessary?

Women are able to initiate divorce through the process of khul‘. This is a form of no-fault divorce referred to in the Qur’an and Sunnah where the husband’s consent was not stated to be required. In these primary texts, the wife is granted the ability to divorce her husband for the simple reason of incompatibility, and there are records of women at the time of the Prophet who married and divorced numerous times. There are also reports of women who married the Prophet but then changed their mind on the wedding night and he granted them divorce without seeking cause.

Over time, however, the majority of Muslim male jurists determined that the husband’s consent was necessary, and most Muslim countries today still adopt these twelfth-century rulings. Interestingly, case law in Pakistan (1967) and legislation in Egypt (2000) returned to the Prophetic practice whereby the husband’s consent was not needed.

If the husband is at fault, women can also initiate a judicial divorce through faskh, tafriq or ta‘liq — whereby in Muslim countries they present their case and prove certain grounds before a court judge. Because this form of divorce does not require the husband’s consent, this is usually the main option women take when they are not successful with khul‘. Given there are no such courts in Australia, Muslim women seek out divorce through community processes involving imams.

Many imams or religious leaders in Australia prefer the husband to pronounce talaq or give their consent to a khul‘, so that they are not responsible for ending the marriage, but in extreme cases of domestic violence they will award women this form of divorce. However, as reported by the ABC in a series of investigations across various religious communities in 2018, a number of Muslim women experiencing domestic violence faced numerous challenges seeking religious divorce from imams. This was in part due to imams having narrow interpretations as to what constituted “domestic violence” and requiring meetings with both the husband and wife present in the same place.

In my research, as well as that of others, imams and community leaders are becoming aware of the dangers presented to women experiencing domestic violence and are working with specialist services to make the religious divorce a safer process for women.

Another option for divorce is that women can specify in their marriage contract her right to divorce through talaq at-tafwid, whereby the husband grants his right of talaq to his wife through delegation so that she can initiate divorce without needing his consent. Contrary to common belief among many Muslims, he still maintains his right of talaq. Given the sensitive nature of mentioning divorce at the time of marriage, many Muslim women are discouraged by their families from including it in their contract for fear that they are seen as not committing to the marriage long-term. There is a long tradition of talaq at-tafwid in countries such as Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, but it is largely unknown and not commonly practised in many other Muslim countries and communities, including in Australia.

What options do Muslim women in Australia have?

The women I interviewed for my research were aware of their rights to khul‘ and divorce through imams, but not many had heard of talaq at-tafwid. However, it didn’t prevent them seeking out other ways in which they could be “completely” divorced by using their civil divorce decree.

Some women who were married overseas started proceedings in religious courts and were able to get a divorce through the system overseas with the help of family members.

“Iman” (all women’s names have been changed here to protect their identity) applied for and received a civil divorce and sent it to her home country of Algeria, because it was accepted as legitimate. She considered their recognition of the Australian civil divorce and subsequent registration as divorced under Algerian laws as a “complete” divorce without needing to engage Muslim community processes for a religious divorce.

Other women who had sought religious divorce through community processes and had been unsuccessful decided that their civil divorce sufficed as a “complete” divorce. “Aisha” felt that the imams were not completely aware of her situation when they refused to grant her a divorce without her husband’s consent, and that she was entitled to one — so once she had gained her civil divorce she felt certain that it was sufficient “in the eyes of God” because her marriage was effectively over and she was legally divorced.

This reflects a ruling issued in 2002 by the European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR), a body of contemporary Muslim jurists who offer new interpretations of Islamic laws specifically for Muslims living as minorities in non-Muslim countries. This ruling or fatwa declared that Muslims who conduct their marriage according to a country’s laws should also comply with the rulings of a non-Muslim judge in the event of divorce. According to the ECFR, a civil divorce can and should be considered as sufficient for a Muslim to have a “complete” divorce. Indeed, in Britain some community processes such as the Fiqh Council of Birmingham have adopted this approach to streamline the many religious divorce requests from women.

My research illustrates that improving Muslim women’s access to religious divorce in Australia requires addressing particular social norms and interpretations of juristic rulings that exist among many Muslim communities in Australia, to ensure that just and equitable outcomes are achieved. The Muslim women I interviewed were able to define their own parameters of a “complete” divorce due to their own determination and resilience, and awareness of how civil divorce can be used to gain religious divorce.

While current Muslim community processes are not always easy to navigate, the research shows that Muslim women value their membership within their religious community. Making women aware of the various options they can access to gain a religious divorce is thus an important way they can claim their religious rights and freedom.

Dr Anisa Buckley is a Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne and the University of Sydney. She is the author of Not ‘Completely’ Divorced: Muslim Women in Australia Navigating Muslim Family Laws.

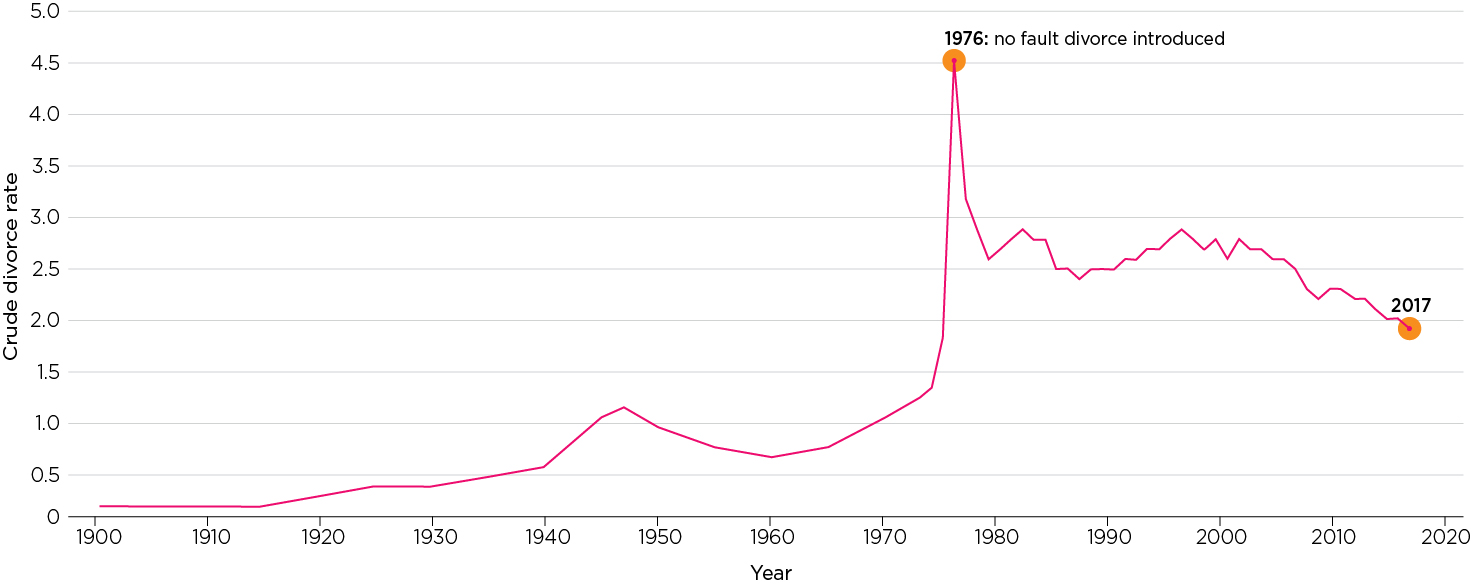

Divorce rates rose in the 1960s and 1970s and peaked at 4.6 per after the introduction of the Family Law Act 1975, which allowed no-fault divorce.

Divorce rates rose in the 1960s and 1970s and peaked at 4.6 per after the introduction of the Family Law Act 1975, which allowed no-fault divorce.

“I’d be lying if I said I saw it coming,” says Emma*. “We were busy parents and professionals. We didn’t really argue. There were ups and downs, but nothing that said ‘unhappy’.”

“I’d be lying if I said I saw it coming,” says Emma*. “We were busy parents and professionals. We didn’t really argue. There were ups and downs, but nothing that said ‘unhappy’.” Three people from a polyamorous relationship are in a batle over how to split a valuable Auckland property after they broke up.

Three people from a polyamorous relationship are in a batle over how to split a valuable Auckland property after they broke up. The Chief Justice of the Family Court has a warning for any parent planning on abusing their custody situation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Chief Justice of the Family Court has a warning for any parent planning on abusing their custody situation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Planning a wedding can feel all-encompassing, and in this age of Instagram, the pressures seem higher than ever to create a picture-perfect day. But getting married isn’t the same thing as being married. If therapists like me had our way, there would be far more preparation and discussion around the latter than the former.

Planning a wedding can feel all-encompassing, and in this age of Instagram, the pressures seem higher than ever to create a picture-perfect day. But getting married isn’t the same thing as being married. If therapists like me had our way, there would be far more preparation and discussion around the latter than the former. Exorbitant housing costs are preventing split couples from making a clean break – more than one in 10 Aussies say they’ve had to live with an ex just to make ends meet.

Exorbitant housing costs are preventing split couples from making a clean break – more than one in 10 Aussies say they’ve had to live with an ex just to make ends meet.