Justice John Fogarty. Photo: Mark Wilson

John Francis Fogarty, who was an outstanding Family Court judge and a significant figure in child protection, has died aged 80. His compassion and humanity shone through all aspects of his life. He did not avoid the difficult issues in society and his life, thus making his contribution so noteworthy.

John Fogarty was born in Benalla, third son of Patrick and Nellie Fogarty, both originally from Koroit, but grew up in East St Kilda. He attended Christian Brothers’ College St Kilda but matriculated at St Kevin’s College because CBC St Kilda did not accommodate year 12 at the time. He was a good but not exceptional student, winning a Commonwealth Scholarship.

John’s father was a railway signalman and expected his son to take a secure job in a bank or the public service. Instead, John was determined to study law, despite family finances precluding full-time study. He enrolled at Melbourne University and undertook the articled clerks’ course, working full-time.

John Fogarty, AM

Judge, children’s rights advocate

9-6-1933 — 3-10-2013

John excelled in those studies, winning the Supreme Court prize for articled clerks in 1954. Rather prophetically, the next year, while still an articled clerk, he contributed the major case note in Res Judicatae (the journal of the Law Students’ Society) with august contributors such as Zelman Cowen and David Derham. The title of the article was ”Divorce – Constructive Desertion”.

He signed the bar roll in March 1956 and quickly developed a wide general practice with an emphasis on civil jury work, testator’s family maintenance and family law. Very much at home in the criminal jurisdiction, he defended the late detective sergeant ”Bluey” Adam, the only accused acquitted in the trials arising out of the Beach royal commission into police corruption.

More significantly, Fogarty was junior counsel to Edward Woodward, QC, in the first Aboriginal land rights case in Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd. This involved many trips to central and northern Australia and left a lasting impression on him. They did not win the day, but principles were established that led to the later High Court decision in the Mabo case.

In addition to his busy practice, John was editor of the Victorian Law Reports from 1969-1976, consulting editor of the Australian Argus Law Reports, author of Bourke & Fogarty’s Maintenance Custody and Adoption Law, and co-author of Bourke’s Police and Summary Offences.

There were many tragedies and hardships in these years. His eldest brother, Kevin, died in 1965 aged 40. John’s first wife, Noel, whom he had married in 1956, died in 1968 from encephalitis, leaving their three sons all aged under 10 years. He was assisted in the care of the children by Noel’s mother. His second marriage to Judy Henry in 1973 ended in 1980.

On February 2, 1976, Harry Emery and John Fogarty were the second and third appointees to the Family Court in Melbourne. John had been very active with Austin Asche, the first judge appointed in Victoria to educate the legal profession before the commencement of the Family Law Act. He sat from early days as an appeal judge in the full court and later as chief judge in appeals.

John Fogarty is generally regarded as the foremost jurist to sit in the Family Court. It was claimed at his farewell sittings that the Family Law Reports contain 280 of his judgments. He was involved in many major judgments in the early 1990s, particularly with the then chief justice, Alastair Nicholson, which defined major aspects of family law.

In 1983, John married Alicia Noonan and the next 30 years were likely his most contented. They established a superb garden at their home in Hampton. Alicia has been a wonderful hostess and Melbourne Cup day at the Fogartys was legendary.

As well as his duties as Family Court judge, John was chairman of the Family Law Council from 1983-86, and chairman of the Institute of Family Studies from 1986-90. As chairman of the Child Support Consultative Group from 1988-89 and chairman of the Child Support Evaluation Advisory Group in 1991, he was instrumental in the creation, establishment and implementation of child support in Australia.

John Fogarty’s interest in child welfare became a dominant theme in his life. He was chairman of the Victorian Family and Children’s Service Council from 1988-91. Due to his experience in the Family Court, he was acutely aware that children in vulnerable situations needed better protection.

In 1989 and 1993, he produced significant reports on child protective services in Victoria. The report on the notorious Daniel Valerio death led ultimately to mandatory reporting of child abuse in Victoria.

John’s interests were many. It is likely that his remarkable intellectual curiosity led him into the uncharted fields of family law and child protection. His love of literature and history, particularly Australian, was evident in his extensive private library.

He enjoyed sport. John’s first serious heart trouble occurred immediately after the siren when Melbourne stormed home to defeat Carlton in the 2000 preliminary final. He was in Epworth Hospital when Essendon thrashed the Demons in the grand final. In later years, John wryly remarked that the only illness likely to be induced by following Melbourne was depression.

He was a member of the Melbourne Racing Club and enjoyed a day at the races, particularly during the Caulfield carnival. He also followed cricket and tennis.

Recognition of the significant contribution made by John Fogarty to Australian society came in January 1992 when he was made a member of the Order of Australia. Other awards were the White Flame Award (Save the Children Fund) and the Community Services Appreciation Award. He was patron of the Centre for Excellence in Child Welfare, the Mirabel Foundation and Family Life, and director of the Trust for Young Australians and the Child Protection Society.

Despite his busy life, John found time for his friends. He enjoyed a weekly lunch when discussion rarely related to work but rather an analysis of the week’s footy, racing or cricket, plus a dose of current politics.

John is survived by his wife, Alicia, sons Peter, Mark and Matthew, and grandsons Balin and David.

Maurie Harold was a senior registrar of the Family Court in Melbourne and knew John Fogarty for 70 years.

DOCTORS can ignore restrictions on late-term abortions in Tasmania without fear of prosecution and potentially without any professional sanction, according to senior legal figures.

DOCTORS can ignore restrictions on late-term abortions in Tasmania without fear of prosecution and potentially without any professional sanction, according to senior legal figures. The number of domestic violence incidents in WA has risen almost 60 per cent over the past four years, with police attending more than 44,000 calls for help in the past year.

The number of domestic violence incidents in WA has risen almost 60 per cent over the past four years, with police attending more than 44,000 calls for help in the past year. If you successfully represent yourself, the costs you can recover from the other party are strictly limited. The appellant in

If you successfully represent yourself, the costs you can recover from the other party are strictly limited. The appellant in

, a

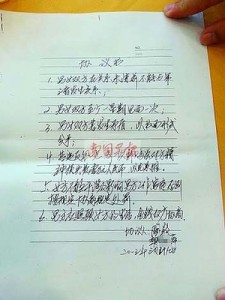

, a  A Chinese official has become an online laughing stock after the publication of a bizarre “love-affair contract” which he had obliged his mistress to sign.

A Chinese official has become an online laughing stock after the publication of a bizarre “love-affair contract” which he had obliged his mistress to sign. A QUARTER of the nation’s health budget is devoted to futile end-of-life care that strips patients of a dignified death and means healthier people have their surgery delayed.

A QUARTER of the nation’s health budget is devoted to futile end-of-life care that strips patients of a dignified death and means healthier people have their surgery delayed. A Parenting

A Parenting