Australia’s Family Court system is in crisis but a new review offers some hope that we can at least take a step towards a better approach, argues family law specialist Jane Miller.

Australia’s Family Court system is in crisis but a new review offers some hope that we can at least take a step towards a better approach, argues family law specialist Jane Miller.

“I feel that the (Family Courts) system is letting the people down.”

These aren’t the words of a heartbroken parent or a furious former spouse following another lengthy, expensive, emotionally bruising encounter with Australia’s Family Court system. No, these are the words of former Chief Justice of the Family Courts Diana Bryant in April last year, who went on to say: “There are very vulnerable people caught up in the system and at the moment we are powerless to do anything about it.”

Her words were echoed by then-Attorney-General George Brandis who stated there was “broad consensus that the system is now in many ways dysfunctional and a comprehensive overhaul is needed”.

These are strong words from two people at the coalface of Australia’s legal system. It is interesting to note no-one defended the system against these criticisms. Perhaps no-one could possibly justify that the current processes to resolve family disputes are working as well as they should be.

Be it client, lawyer, social scientist, judge or politician, there is a unified voice resounding across the country that it is time to re-write the policy book for family law. This change is coming in the shape of the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) review into the Family Law Act, which the Federal Government announced late last year.

So what does this Family Courts dysfunction actually look like?

The finger-pointing about where the fault lies is in all directions. Insufficient government funding, adversarial lawyers, court inefficiencies and too much focus on blame and not enough emphasis on solutions form part of the problem. Meanwhile, criticisms abound in relation to delays, prohibitive costs, complex structures and injustice. All of these factors serve to rub more salt deeply into the emotional wounds of broken families.

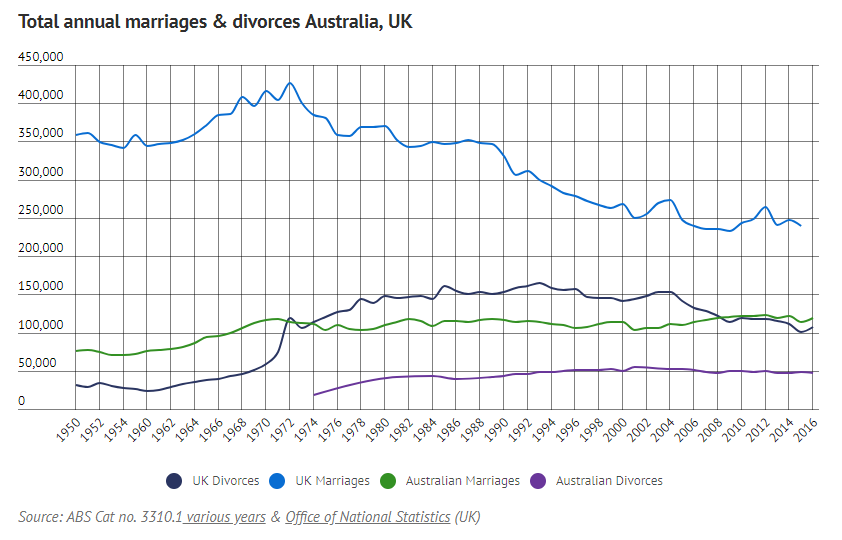

Added to this is the sheer scale of Australians interacting with the family law system. The review reported that in 2016 there were 46,604 divorces in Australia, involving 40,202 children under 18. There is no specific data as to the number of long-term de facto relationships that end annually, or the children of those relationships.

However, it is easy to estimate that at least 150,000 Australian adults and children are subjected to family break up each year, adding up to one million Australians in the space of just six or seven years, and a heavy proportion of our population for our legislators to consider.

There are literally not enough courts and judges to keep up with demand and waiting times have blown out.

These problems aren’t new and the family law system in Australia is no stranger to scrutiny and reform. Since 1975 we have witnessed so many piecemeal amendments to the Family Law Act, court rules, forms and processes that one wonders if the family law system is the Sydney Harbour Bridge of the Attorney-General’s office: no sooner has one round of reform been implemented than it is time to embark on another reform.

However, despite best attempts, the shortcomings of the system have continued to obstruct access to justice and we have now reached the tipping point. I, like most family lawyers, welcome the ARLC inquiry and the opportunity for real change.

This latest review is being spruiked as the largest in more than 40 years. It has been met with cautious optimism by lawyers that we will see positive and meaningful change in our system. However, the scale and magnitude of that change will remain unknown until the ALRC releases its discussion paper in September 2018 and final report in March 2019.

So, why does family law regularly attract the attention of legislators for law reform?

Other than the criminal justice system that can deprive a person of his or her freedom, no other system of law cuts as close to the heart as family law. The system encourages separating couples to negotiate their own outcomes, but if this is not possible then the legislation puts the power in the hands of judges to determine disputes.

Judges are empowered to make parenting decisions for parents that cannot reach a consensus. The scope of these powers is wider than the “if, how and when” a child will see their parents. These decisions can include a child’s school, whether the child should undergo a medical procedure, if the child should have a relationship with a person who has been accused of child abuse, and much more.

Judges can also make financial decisions for couples unable to agree upon the division of their assets. This can have significant implications for both parties’ financial wellbeing, including their standard of living, housing options and when retirement might be affordable.

All of this strikes at the core an individual’s personal liberty. The stakes are high and occur in a context where most of the evidence is obscured behind closed doors. This gives family law an emotionally raw edge. It is about real people with real problems – and that demands the attention of lawmakers.

There is also the need to protect the vulnerable, such as victims of family violence. The power imbalance of parties involved in a relationship break-up is often gravely disproportionate, and threats to personal safety can be heightened after a separation.

We must next ask whether this is the reform to end all family law reforms? Will this provide the magic cure to the system’s ills, eliminating the need for subsequent reviews?

The short answer is no.

Our family law system isn’t being overhauled now because it was “wrong” in the first place; it is being overhauled because it has become outdated and inefficient in the delivery of timely justice. Society has outgrown it.

Any legal system must change with its people and society. Changes in community values will pre-empt what future policymakers do with family law well beyond 2018/19 and the release of this review.

There is a diverse group of people engaging with family law today: those with disabilities and mental health concerns; those impacted by social and economic disadvantage; people with substance dependencies; parties of varying cultural backgrounds and those with language barriers, to name a few. These evolving diversities will warrant a progressive legal system that responds to human needs. On top of this is the increasing diversity of families: changing gender roles, same-sex relationships, surrogacy and grandparents as primary carers.

This diversity could never have been anticipated when the family law system was last overhauled and, likewise, we in 2018 cannot predict what future family units may look like. Future law reform is inevitable because, try as we might, we are never going to arrive at a perfect system.

The existence of the family law system itself is a “necessary evil” – a product of human suffering, failed hope and the bitter conflict that comes from lost dreams and broken hearts.

While many clients come seeking justice and restitution of their hurt and loss, they often exit the system feeling despondent that the process did not “right the wrongs” endured in their most intimate relationships.

Sadly, ALRC review or not, there is no legal solution that is wholly capable of fixing what are, in fact, social problems. Hurt, deception, betrayal and conflict cannot be healed by a legal band-aid. As a result, there is an inherent ceiling to the levels of “customer satisfaction” that punters can expect from the family law system.

To overcome this our legislators must be astute, sophisticated thinkers, well-informed about the tremendous complexities and diversity in family law. They must be attuned to the evolution of the family unit which, judging by past experience, will continue to develop in ways we cannot even contemplate today.

Our family law system will need to change, respond to and move with changes within our families and within society as a whole. As a result, as welcome as it is, this will not be the reform to end all reforms, but a much-needed first step towards a system that helps, rather than hurts, families.

Individuals may share their experiences of family law with the ALRC review. Individuals who have a story to tell are welcome to do so confidentially at the ALRC ‘Tell Us Your Story’ page, or may make a submission in response to the Issues paper by 7 May 2018.

Jane Miller is a partner at Tindall Gask Bentley Lawyers and an accredited Family Law specialist.

The Family Court and Federal Circuit Court will be combined as part of sweeping changes to the financially and emotionally crippling family law system, in an announcement by the Attorney-General Christian Porter today.

The Family Court and Federal Circuit Court will be combined as part of sweeping changes to the financially and emotionally crippling family law system, in an announcement by the Attorney-General Christian Porter today. It’s been 18 months since Anne last saw her grandchildren.

It’s been 18 months since Anne last saw her grandchildren. A family court

A family court  However, the

However, the  The couple officially divorced in 1995 and the Family Court made orders awarding the former wife $164,000, which equated to about 38% of the asset pool of the

The couple officially divorced in 1995 and the Family Court made orders awarding the former wife $164,000, which equated to about 38% of the asset pool of the  Royals

Royals

EWith the increasing proportion of people aged 65 and over, the problem of elder financial abuse is a growing concern.

EWith the increasing proportion of people aged 65 and over, the problem of elder financial abuse is a growing concern. Australia’s Family Court system is in crisis but a new review offers some hope that we can at least take a step towards a better approach, argues family law specialist Jane Miller.

Australia’s Family Court system is in crisis but a new review offers some hope that we can at least take a step towards a better approach, argues family law specialist Jane Miller.