It is generally when tragedy strikes that you wished you had taken the necessary precautions to protect yourself from financial disaster.

It is generally when tragedy strikes that you wished you had taken the necessary precautions to protect yourself from financial disaster.

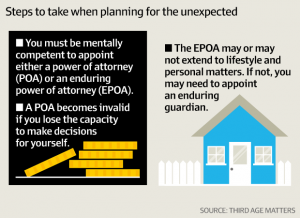

The appointment of someone you trust to make critical financial – and possibly life-changing – decisions on your behalf in the event that you can’t make those decisions for yourself is also time critical. Because once you lose capacity, you can no longer appoint that person.

An enduring power of attorney is the “insurance policy” that most people get wrong – it’s the document used to appoint someone else (called an attorney) to legally deal with your money, bank accounts and other assets if you become unable to manage your affairs by yourself.

It’s not just elderly people who need to think about this, it’s all of us.

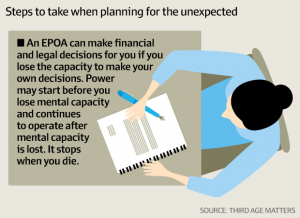

The power in the document in most cases starts when you lose capacity – either temporarily or permanently. It ceases when you die. After that, your will kicks in.

With dementia rates on the rise, this condition gets maximum attention. But capacity can be lost through car accidents, workplace incidents, ill health, psychiatric illnesses, during medical operations, through strokes and being in a coma. Illness doesn’t discriminate between ages.

“It is just as easy for an old person and the young to lose capacity,” says Brian Hor, special counsel with Townsends Business & Corporate Lawyers. “No one knows when it might happen so it is better to be prepared.”

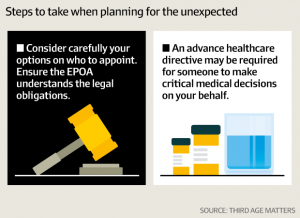

Being prepared is to understand what you are doing when you appoint an attorney, what the options are and that the person or persons chosen are the best possible, says Rod Cunich, consulting principal of KeyPoint Law.

“People often make the mistake that abuse is limited to something that is intentional and underhanded,” he says. “There are [people appointed as] attorneys out there who abuse their power and rob their parents in full knowledge of what they are doing, but there are other cases where they are naïve and doing the wrong thing.”

The misuse of an enduring power of attorney can come in different forms. For example Jim (not his real name) who is 87 is finding it difficult to get to the bank to pay his bills and withdraw money. After a visit to his solicitor he appoints his daughter Jane as his enduring power of attorney with the powers to start immediately.

Using her powers, Jane is able to become a signatory to Jim’s accounts. She also has access to his internet banking. The arrangement is working well until Jane has some big bills of her own to pay and gets behind in her mortgage payments. At the same time she is paying Jim’s bills and doing his banking, she withdraws some cash and keeps it for herself.

Jim doesn’t check his bank statements and has no idea his cash reserves are running low until it comes time to move into residential care and there are insufficient funds to pay the costs.

Who to appoint

So who can you trust? Spouses and partners generally appoint each other and, as a backup, one or more of their children. It can be set up so the attorneys can make decisions jointly or independent of each other.

Other options include the appointment of a professional such as a solicitor or accountant or a professional person jointly with a family member or friend.

It may be that two or more trusted and competent family or friends are appointed and required to make joint decisions which may reduce the risk of abuse.

There is no perfect solution and they all come with their pros and cons, says Cunich.

He says the safest way is to appoint a professional but that may come with costs, have an element of inconvenience or delay and if parties can’t agree there will be a deadlock which may be hard to resolve.

“The most efficient and cost-effective appointment is a sole person (family or friend) but this maximises exposure to risk/abuse,” he says.

“These people have your finances, and in some cases your very life, in their hands,” says Natalie Abela, a Partner at law firm Cowell Clarke. “It must be someone you trust implicitly and who knows you very well – preferably someone who is financially savvy and who is not in conflict with other family members.”

Natalie Abela a says the more instructions and clarification of your wishes you can provide to the designated person the better.

Telling the rest of the family about the appointee is also important so when the time comes, everyone is clear on who is responsible and has authority in making vital decisions, she says.

Forms to appoint an EPOA are readily available over the internet. But like a do-it-yourself will kit, most people “don’t know what they don’t know” and there are plenty of risks in appointing the wrong person or persons, says Rod Cunich. It is complicated by the law being different in each state and territory.

The powers of an attorney

In most states and territories, an attorney’s powers stop at financial and legal decisions – for example, spending money to pay medical and household bills.

When it comes to lifestyle and personal matters like whether to remain in your own home with help or move into residential care and which doctors to appoint or personal services to use, you may need to appoint what is calld an enduring guardian.

In some jurisdictions like Queensland, ACT and Victoria, an enduring power of attorney extends to decisions about lifestyle and personal matters and covers the role of enduring guardian.

However, a further thing to check is whether the document enables the attorney or guardian to direct how medical treatment is administered within, say, a hospital.

It may be that a further document such as an advance healthcare directive (also referred to as a living will) is required. This would include decisions around whether to attempt to resuscitate you in the event of cardiac arrest or turn off life-preserving machines.

Hor says it makes sense to appoint an enduring power of attorney at the same time as enduring guardian if necessary.

“Doctors may listen to family members about medical-related issues but there is now recognition that there is a formal role,” he says. “If there is an enduring guardian or an advance care directive in place and a person’s wishes are well-documented, then their views are likely to trump those of a family member who can make informal suggestions.

If you don’t choose

Where there are joint assets with a spouse or long-term partner, do not assume that they can make decisions on your behalf without being appointed your attorney and/or guardian, says Hor.

“Without an EPOA, there is no one who has the legal right to deal with your assets such as your bank account or selling your jointly-owned property. They cannot sign documents for you without it,” he says.

If someone has not appointed an EPOA and loses capacity and there are decisions to be made around their finances and their health, then an application has to be made to the relevant state tribunal to appoint a guardian.

If there is a decision to be made, such as needing access to their money to pay for medical expenses or care, then family members may have to seek the permission of the appointed guardian.

Rod Cunich says in addition to this being a time-consuming and stressful exercise, financial guardians (even if they are a trusted family member) may have to pay a security bond as a condition of being appointed.

At worst, a tribunal may appoint a stranger as guardian or a trustee company where significant fees must be paid, he says.

Problem areas

The law states that the attorney must act in the best interest of the principal (ie, you) and avoid conflicts of interest.

Rod Cunich says common problem areas are when attorneys fail to keep accounts or they make unauthorised transactions – whether on purpose or inadvertently.

“There is no power or authority to give gifts to third parties unless expressly authorised by the document and there is no power or authority for attorney to benefit themselves, unless specifically authorised by the document,” he says.

By way of example, Rod Cunich says a child who is caring for their mother and is required to drive her regularly to medical appointments and do her shopping might feel their car is not up to the job, so they use her money to buy themselves a new one.

“They may genuinely believe they are doing nothing wrong even though it is absolutely wrong. It might be greed or naivety or a sense of entitlement and it may not be an evil motivation but it is a breach of the law,” says Rod Cunich.

Where someone believes an appointed attorney is not acting in someone’s best interests, they can apply to the relevant state or territory tribunal to have them removed. Elder abuse can be reported to relevant organisations in each state and territory.

Stay Informed. It’s simple, free & convenient!